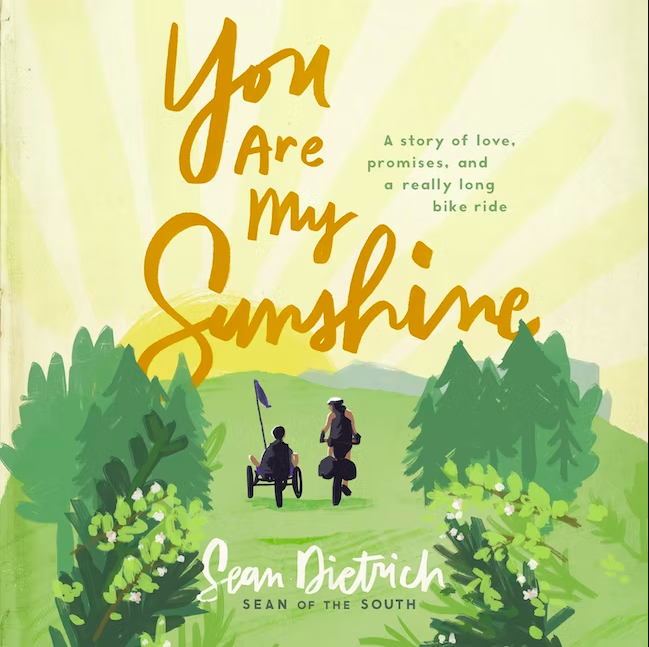

How My Wife’s Cancer Diagnosis Inspired a 400-Mile Bike Riding Trip

“Love is friendship that has caught fire. It is quiet understanding, mutual confidence, sharing, and forgiving. It is loyal through good times and bad times. It settles for less than perfection. It allows for human weakness.”

–Ann Landers

*

A doctor found a lump in my wife’s left breast and multiple masses on her ovaries. We hadn’t been married long. We were young. We still looked like youthful little Kewpie dolls. Our lives had been going great. We were poor but happy. And now we were talking seriously about the c-word. The next thing I knew we were sitting in a medical office waiting room, where I watched a toddler play with wooden blocks and try to eat an entire Woman’s World magazine that predated the Mesozoic era. Before long, we found ourselves seated in a tiny exam room listening to a doctor use medical-sounding words that froze my blood, words I never thought would apply to us, words like biopsy and lumpectomy. Then he threw out the words mastectomy and oophorectomy.

“But it’s still too early to tell,” he added. “We need to do tests.”

“Tests,” my wife, Jamie, and I said in unison.

He smiled weakly.

“You mean like multiple choice?” said my wife.

“Not exactly.”

There was that cool, professional smile again. It looked like he’d practiced this face in the mirror a lot.

The doctor was nonchalant about what was ahead. To him this was just another day at the mill. But to us, this information was nuclear. He held the scans up to the light, pointing at them, rotating them, talking in doctor-speak. But I couldn’t hear a word he said. To me, he sounded like Charlie Brown’s schoolteacher. All I could think about was my vibrant wife. I was in a state of—I don’t know—shock, although it also felt a little like paralysis.

I excused myself while the doctor taught my wife how to pronounce ovarium inferum, performing another inspection on her. Before I left the room, my wife said nothing but locked her eyes on mine. She made an unmistakable gesture that is common in my family. She held up a hand—thumb, index, and pinky extended; middle fingers down. This is sign language for “I love you.”

I returned the salute.

I stood in the hall and doubled over.

I was about to puke. My mouth was dry, my chest was tight, the ambient temperature dropped. I saw myself in a mirror. My complexion had gone white, like someone had sucked the color out of my youthful world. I felt like I’d aged fifty years.

I hate going to the doctor. I hate being subjected to medical care. I hate needles, blood pressure cuffs, tongue depressors, and the medieval test where they tell a guy to turn his head and cough. But the thing I dislike most is the waiting. Everything in the world of modern medicine is based on waiting. Go call this doctor. Wait for a callback. Now call that doctor. Wait some more. Call this specialist. More waiting. Sorry, the specialist is booked solid—you’ll have to wait fourteen more months. May I see your insurance provider information? Which credit card will you be using, sir? I’m gonna need your copay, policy number, Social Security number, and the blood of a nanny goat. Please sit down; the doctor will be with you shortly. And by “shortly” they mean sometime before the installation of the next pope.

The next weeks and months were a miserable time to be alive. Fear was our main emotion. We never knew anything for certain about what lay ahead, and our minds became our perpetual tormentors, always racing toward the worst-case scenario between tests.

There was a lump in my wife’s breast and growths on her ovaries.

The doctor’s words kept replaying in my mind, akin to an old Bob Wills record I once had that skipped whenever it got to “Cotton-Eyed Joe.”

Had not’a been for Cotton-Eyed Joe,

Had not’a been for Cotton-Eyed Joe,

Had not’a been for Cotton-Eyed Joe,

My mother finally threw that record from a second-story window like a Frisbee, achieving incredible distance for someone who, let’s be honest, threw like a girl.

The doc said it might be this. It might be that. She might be okay. She might not. After about a month, I was experiencing something that amounted to moderate psychosis. I couldn’t focus. I couldn’t read books, watch movies, or carry on normal conversations without thinking about that one word in the back of my brain. And the weird thing was, my wife and I became very good at not talking about the worst possibilities, even though they were present in each unspoken word or emotion that passed between us.

Finally, the fateful morning came when I drove the math teacher to the hospital for her first experience under the knife. They called it a “procedure,” a frightening word. The most important human in my life was having a procedure. Lord have mercy.

I’ll never forget the drive to the hospital. The mist was covering the old Florida road. Our chipped Gulf Coast highway was first commissioned in 1934, originally stretching from Apalachicola to Pensacola. At 671 miles, US Route 98 is the longest road in the Sunshine State. And yet that morning it felt about as long as my driveway.

The next weeks and months were a miserable time to be alive. Fear was our main emotion. We never knew anything for certain about what lay ahead, and our minds became our perpetual tormentors.I sat behind the wheel in a trance. The woman beside me held my hand tightly. I kept my eyes on the road and tried to remind myself to keep breathing. She needed me to be strong, that’s what I kept telling myself. That’s what my friends kept telling me. Be strong. Be a cheerleader. Don’t jump to conclusions. Stay positive. Everything will probably be fine.

But what if things weren’t fine? What if the person I loved most on this earth was being killed slowly and invisibly? I have too many family members who have died from the c-word, even more friends. Within a year, I had seen six people I love succumb to or suffer with cancer. Cancer does not discriminate. It kills children and grandparents alike.

We parked in the hospital parking lot. I shut off the car.

Why did time seem to be moving so fast? I looked at my wristwatch and thought about tossing it like my mother did with the Bob Wills record.

Soon Jamie and I were walking across a parking lot toward the towering hospital, holding hands tightly. Then came an awkward moment, just before entering the sliding doors, when we had to release hands so we wouldn’t look like the kinds of fools who sit on the same side of a restaurant booth. We released. And for some reason, this letting go of hands was difficult. I can’t explain why. As long as we were touching, things seemed a little better. But when we let go, this now made us two non-touching, ordinary people, adrift in the merciless world.

The thing is, I have never seen us as ordinary people. We’ve always been Jamie and Sean. Always in that order. Always said together. Some of my wife’s high school students, however, knew me as Mister Jamie, and many of my wife’s friends never even bothered to learn my name. They just called me Jamie’s husband, or Whatshisface. I’ve always been okay with that. The most identifiable trait about me has always been her, and I wear this with pride.

My wife is loud, confrontational, type A, hyper-organized, and uses language that undermines the Southern Baptist Convention. She can hold more beer than I can and sing the national anthem louder than me. She understands the onside kick better than most jayvee quarterbacks, and she can prepare an entire squadron of pound cakes wearing a blindfold. She can captivate her second-grade Sunday school class with three words, and she is beloved by all who were fortunate enough to study math beneath her.

My wife and I tend to be animated people, and we appreciate humor. In social situations, we have our Burns-and-Allen routine down pat. We play off each other when our audience is hot and will do almost anything for a laugh. We are simple people. We get along. We disagree hard. We live in a small house. We drive old cars. We use coupons. We shop at thrift stores. We are dog lovers whose clothes are covered in dander and hair.

This woman also saved my life. Before her, I was a suicide survivor, a dropout, a construction worker, a beer-joint musician with a considerably dim future and with realy pour grammer. Jamie helped me get through college; she told me I was somebody; she tutored me in algebra, trig, liberal arts math, and the systematic, academic hell that is statistics.

We finish each other’s thoughts, read each other’s minds, fight each other’s battles, and nobody has ever beaten us at a game of Taboo.

Taboo, for anyone who is not familiar, is a board game wherein you draw a card with a key word on it, and the object is to coax your partner to guess this word without using the hint words on the card. Our typical Taboo game goes like this:

“Okay, Jamie, this is a thing that—”

“Kangaroo.”

“Right. Okay, next card. Now this is something you—”

“The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.”

“Time’s up.”

Violent high five.

After we walked into the sterilized air of the hospital, a nurse took my wife’s blood pressure and attempted to make small talk. Next the nurses made my wife remove her clothes and put on one of those horrible gowns. We live in the twenty-first century. We have robotic medical devices capable of performing surgery manned by a doctor 4,100 miles away. And yet patients still wear cheek-revealing gowns that predate the Dark Ages.

Jamie was soon in a wheelchair, reading a National Geographic, ready to be escorted to the place where biopsies happen. I sat beside her in a sticky vinyl seat, drumming my fingers on an armrest. I was sick. I ignored the TV in the corner blaring episodes of Judge Judy at a volume loud enough to crack porcelain. And I was trying a little too hard to be upbeat.

“It’ll be fine,” I said.

She drew in a breath. “Right.”

“Over before you know it.”

“Yes.”

“They do this kind of thing every day.”

“Every day. Right.”

“Just a routine thing.”

“Yes.”

“Nothing to worry about.”

I was a bad liar. What I really wanted to say was “I love you.” But I’d already said it 12,203,291 times that morning, and I feared those three words had started to lose their impact.

I wanted to be the one in that wheelchair. I wanted to save the day for my wife. It should have been me going back there to be poked and sliced open.

My wife absently turned a page in her magazine. “I wanna do something fun.”

I nodded.

“Something big,” she said. “Something together. Something really . . . big.”

“Like what?”

“Something—I dunno—big.”

Judge Judy was tongue-lashing the defendant.

I was reminding myself to breathe.

She looked at me. “I’m thinking something wild. Something really, really . . .”

“Big?”

“Exactly. Something crazy.”

“Like a reverse mortgage?”

My heart was not in our conversation, but I wanted to keep her talking.

“Okay, sure, sweetie,” I said. “Whatever you want. We’ll do something . . .”

“Big?”

“You bet.”

The second hand on the clock was clicking. Judge Judy was tearing into the prosecution now. I realized I was wringing my hands.

My wife held up the magazine and tapped the page. “How about doing this?”

The glossy photo spread showed images of a trail cutting through deep woods and mountains, across rivers and creeks.

“This looks fun,” she said.

I didn’t answer at first because I was confused. My wife and I are not outdoorsy people. We’re more Krispy Kreme enthusiasts. Even so, I smiled. “Whatever you want, honey.”

“We could camp out,” she said. “Sleep under the stars, and you know . . . it could be really fun.”

“Sure.”

“You’d do it?” she said.

I looked at the magazine closely. The pictures showed something called the C&O trail. I’d never even heard of it.

I nodded. “Why not?”

“Seriously?” she said. “You think we could do all one hundred and eighty-five miles?”

“Wait. How many miles?”

“One hundred and eighty-five.”

“Um. Maybe,” I said.

She smiled. “You’d really do this for me? You swear?”

“Well, let’s not start swearing.”

“Swear to God.”

“Honey.”

She plopped the magazine into her lap. “I knew it. You’re just telling me what I want to hear.”

“Alright. I swear to God.” My Baptist mother would have disowned me.

Thus satisfied, my wife read through the magazine article while I watched her beneath the glow of the harsh lights and nearly cried.

The nurse finally came into our little room and gripped the handles of Jamie’s wheelchair. She handed me the magazine. I released my wife’s hand once again and felt my chin start to quiver dangerously. I followed the wheelchair down the hallway, spewing more nervous chatter. I could see the math teacher nailing a brave smile to her face. I kept pace alongside her chair until we arrived at two foreboding doors labeled “For Authorized Personnel Only.”

This woman saved my life. Before her, I was a suicide survivor, a dropout, a construction worker, a beer-joint musician with a considerably dim future and with realy pour grammer.The nurse turned to me. “Sorry, sir, this is as far as you go.” The lady mashed a big button on the wall, and the doors swung open. And they took my wife away from me.

“We’re going to do something big!” I called out behind them, holding up the National Geographic. “Something really big! This will all be over soon! You’ll see!”

The doors closed.

The last thing I saw was my wife’s hand, raised in an unmistakable gesture. Index, pinky, and thumb extended. Middle fingers down.

“I love you too!” I shouted to steel doors. But there was no answer.

It would take us many years to make good on our promise. But we would do it. One day, in the far-flung future, our two softened, middle-aged heroes would find themselves undertaking an American trail, traveling a lot farther than a mere 185 miles. Together, my wife and I would attempt to cover approximately 400 miles, traversing four states. We would endure wind, rain, sleet, and public bathrooms. We would live out of backpacks. We would eat a lot of energy bars that tasted like wet napkins. But we were together.

And that is where our story begins.

______________________________________________

Excerpted from You Are My Sunshine. Reprinted with the permission of Zondervan. Copyright © 2022 by Sean Dietrich.