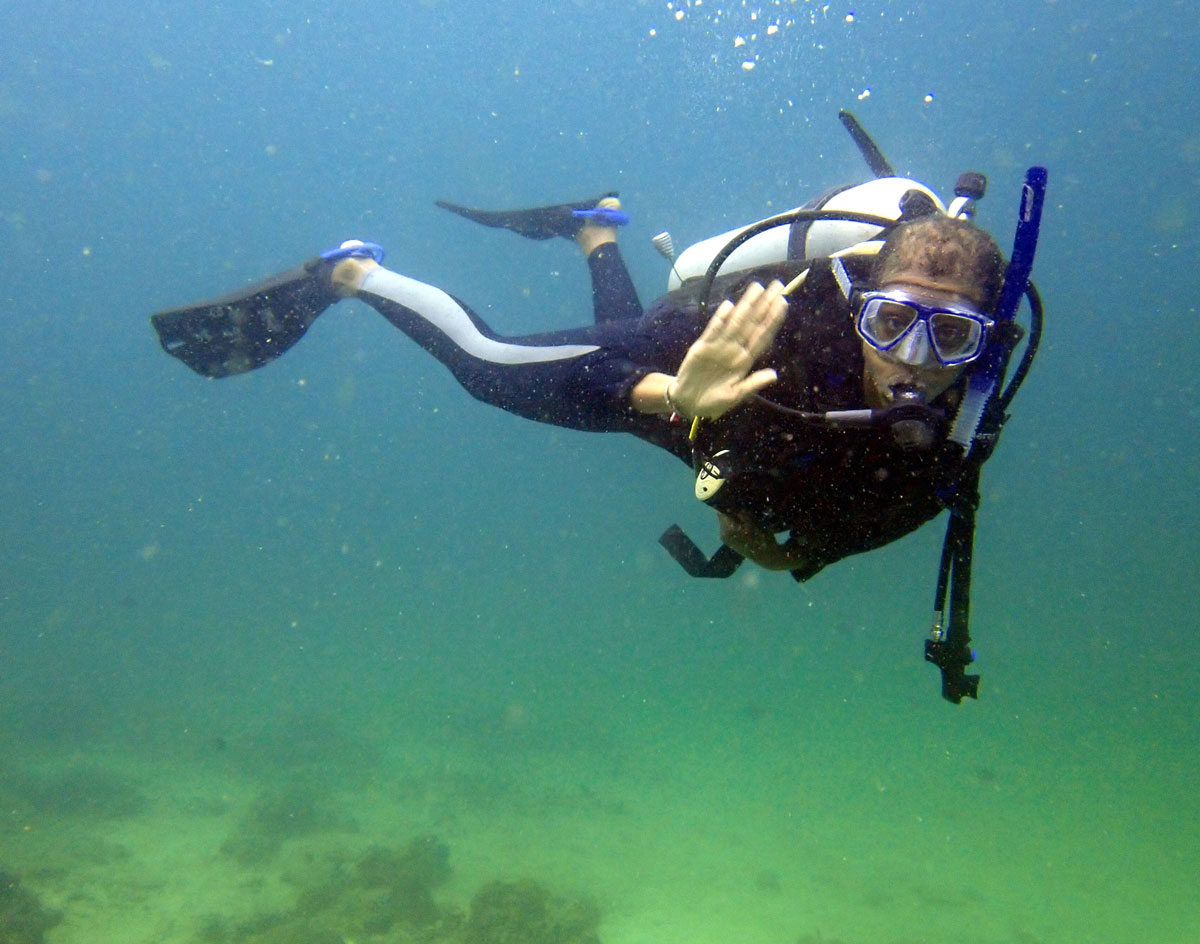

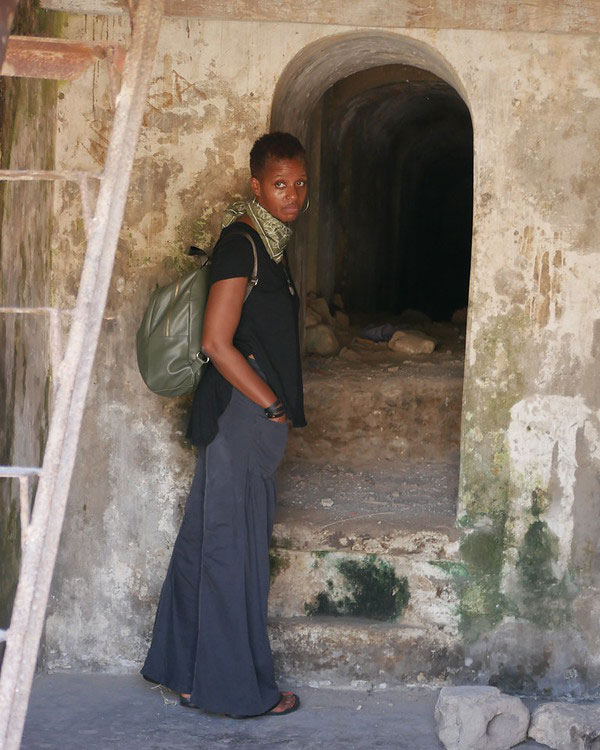

National Geographic Explorer and podcaster Tara Roberts on diving for slave shipwrecks

Photograph by Arjaree KC Gang

Tara Roberts has no fear of depth. The journalist and Atlanta-native cut her teeth at publications like Essence and CosmoGirl magazines before deciding to travel the world and write stories about change makers and social entrepreneurs. She’s spent the last few years following and diving with Black scuba divers as they document slave shipwrecks around the world. She describes the ocean floor as peaceful, meditative, and magical—“like being an astronaut walking on another planet.”

As a National Geographic Explorer and Storyteller, Roberts retold those stories in her six-part podcast series, Into the Depths, and, in the process, found a way to honor the lives of lost ancestors. Below, she talks about what inspired the project, the global impact of the slave trade, and how uncovering world history led to discoveries about her own family lineage.

Brenda Altmeier (NOAA)/Courtesy of Chris Searles

Your introduction to these diving missions started with the organization Diving with a Purpose. Tell me more about what inspired you to chase this story?

I was living in D.C. and happened to go to the National Museum of African American History and Culture. I saw a picture of a group of primarily Black women on a boat in wetsuits, and I simply had never seen a picture of a bunch of Black women in wetsuits before. So, it stopped me. I found out that they were part of this group called Diving with a Purpose, and that part of their mission was to search for and help document slave shipwrecks. I was like, What? There are people who look like me doing this? It really spoke to me and captured my imagination.

Diving with a Purpose is full of volunteers who do this work. Nobody’s paid for it. They’re just regular people who want to scuba dive. Anybody can participate—you just have to have an interest in scuba diving and be willing to do some training.

You not only spoke to these divers, but you did the training, went into the depths of the ocean, and helped discover history alongside them. Why was it important for you to be so completely immersed in this process?

I didn’t want this to be a he/she/they story; I wanted it to be an I/we sort of story, and the only way that it could be that is if I was a part of it, too. It was important for me to touch and confront that history myself, to go under the water and experience the atmosphere of the ocean, and to know what it’s like to uncover history. I wanted to know what that would feel like for me, how would it impact me. Would it change anything?

I think there’s some power in being able to tell a story about history that directly impacts you. Many of our historical stories, especially about the slave trade and slavery—especially the ones that are in the mainstream history books that we grew up with—they’re always some outsider talking about it or somebody who’s also not Black telling that story. But I thought it was just really important for me to talk about that history from my own lens as well.

Some might argue that it’s time the nation moves on from conversations about slavery. There’s sometimes an attitude of, We know, it happened, move on. Why is it important to revisit this history?

Well, I would say that most people likely know very little about the slave trade. The slave trade itself is different from slavery—from what happened once people got on the shores. For instance, there were 36,000 voyages that brought 12.5 million Africans to the Americas over those 400 years. Experts estimate as many as 1,000 of those ships wrecked, but to date, less than 20 have been found. Already, you’ve got this enormous amount of history that just hasn’t been uncovered.

A lot of people might think, Oh, it’s Black history, whatever. It’s not Black history. We’re talking about four continents involved in this trade for 400 years: Europe, Africa, South America, North America. The slave trade was one of the most monumental events in human history. Entire landscapes changed. Wealth was built, wealth was diminished. Powers grew, powers fell.

There’s so much to unpack, but because we approach it with so many emotions—so much shame, so much guilt, so much anger—there’s a way that we can’t look at it.

Photograph courtesy of Tara Roberts

What was the most difficult aspect of the training to take these dives?

So, there’s the training to be a scuba diver, which is its own thing, and then there’s the training to map a shipwreck. And all of them have an element of math to them. And what’s weird is I actually used to be good at math in elementary school, but those days are gone! I am not exact anymore. I’m just not.

That’s why a lot of the divers do come from more technical backgrounds. [Some of my] instructors have been engineers or civil servants. There’s a kind of right-brain leaning mindset, and I found that’s tricky for me. I also have some trouble equalizing my ears; I’m always struggling with that, so it takes me a little bit to actually get down.

In episode 3, you go to Costa Rica and meet a team of young divers from the community actually doing the diving themselves. What does it mean for a community to be involved in discovering their own history?

What often happens when archaeologists, historians, or even divers from outside of the community come into a place to do this work, they leave and take their research with them. They publish it in journals that the community doesn’t have access to, and none of the funding that might be generated makes its way back into the community.

But now, in Cahuita, there is a museum that the community put together with artifacts from the dive. The University of Costa Rica has worked with Ambassadors of the Sea to create a degree program around diving so that more people from the community will get the skills to do this. Some of the young people founded an organization—Puerto Viejo walking tours—and they are giving tours to tourists that include snorkeling and share more about the shipwreck. The National Museum of Costa Rica is planning an exhibit that’s about the shipwrecks in Puerto Rico. A number of the divers who started when they were 14 years old and are now 21 to 22 years old are thinking of careers that include diving or the ocean in some way. And, finally, María Suárez Toro [the journalist and educator leading this project in Costa Rica] insists that the community is at the forefront; she insisted that the young people who participated in this research be listed as authors on papers generated from this research, so it gives them the credentials to be seen by the outside world.

All of those are examples of what happens when a community is empowered to find its own stories and to use its own stories to further its advancement.

Photograph courtesy of Tara Roberts

In the final episode of the podcast, you start doing research into your own family history and learn more about your great-great-grandfather Jack. Since the podcast has ended, have you continued that research? Any new discoveries?

My uncle just called me, actually, and told me that he thought that Jack’s son might have also fought in the Spanish War! We need more information to confirm that, but it’s gonna take a lot more time and energy to really do more legwork. What the genealogist started off doing is [looking for] any information that might lead us to Jack’s parents, and we haven’t gotten there yet. If we’re able to find that record, it might list his mother and father, which would then take us back perhaps to the 1700s, which would be amazing!

Do you have any advice for someone who wants to research their family tree but might not know where to begin?

There are associations of African American genealogists all over the country who are passionate about African American history and can be hired if you’ve got some funding to put towards this. Sometimes it’s a great idea for the family to come together collectively to pay a genealogist. But the first place to start is to talk to the elderly people in your family and get those stories before they’re gone and those stories are lost forever. That’s the free way to do it.

Photograph courtesy of Tara Roberts

You talked about how so much emotion is involved in our understanding of the slave trade. What has this story taught you about the process of healing from such difficult history?

Many of the stories that we tell are centered in the pain and trauma of the slave trade, and so it’s almost impossible to see individual lives and to see the humanity inside of these people. That’s what I would argue is missing from these stories, and if humanity is missing, then how do we do the healing? How do we really connect to what happened in the past? How do we move beyond concentrating on the pain?

My mother had [a] picture of Jack on the wall for years, and I would walk right past it. He was born in 1837, and [I’d think], No, that’s just too much. But then to find out these details about Jack—that he was an activist, soldier, and real estate investor! I also found out that he might have owned a speakeasy. And I don’t know what happened in that speakeasy! (laughs) I’m sure it was all kinds of disreputable stuff, but I love it. It means Jack was human. His life wasn’t just about enslavement. It wasn’t just about the horrors. There was life inside of that and that gives me something to connect to him around. That’s what’s available for all of us as we ask more questions.

When we take the moment to acknowledge and to honor [our ancestors], it heals something inside of us, a wound that I think many of us don’t even know is there. There’s an opportunity for resolution, for completion.

The post National Geographic Explorer and podcaster Tara Roberts on diving for slave shipwrecks appeared first on Atlanta Magazine.