On Jane Austen and The Lovable Unlikability of Emma Woodhouse

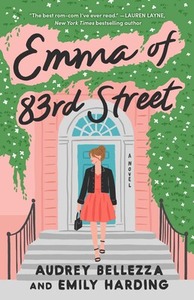

When my friend Audrey and I decided to write Emma of 83rd Street, a retelling of Jane Austen’s Emma set in modern-day New York City, I immediately printed out one of my favorite Austen quotes and hung it on the wall of my office.

“I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like.”

According to her nephew, Austen said this about her titular character just before she embarked on writing Emma, so it felt apt to display it over my cluttered workstation. Her words remained there throughout the writing process, a constant reminder that this story–despite being beloved for over 200 years, revisited and reimagined countless times—still needs to be anchored to one overriding truth: Emma Woodhouse is unlikable.

Now, that may seem unfair. In fact, I think I can actually hear the collective gasp from my friends and fellow Austenites as they get ready to point out that, yes, while Emma might be spoilt and vain, she’s also intelligent and self-assured, with an innate kindness that allows for her humility to grow over the course of the novel. Doesn’t that count for something? And I would heartily agree. But that doesn’t mean Austen was wrong. In fact, her statement was prescient, and key to why so many of us still love Austen today.

I am a life-long Jane Austen fan. I blame the tattered copy of Pride and Prejudice I found in the school library in 8th grade which I inhaled over a 48-hour period. It was an obsession only further cemented by Emma Thompson, Gwyneth Paltrow and Alicia Silverstone; my adolescent years were flooded with Austen adaptations that worked my VHS player to the brink. Was it the costumes? The swoon-worthy romance? I didn’t have time to consider—I was hooked.

That love has only grown over time. Now there are heated debates with friends over a bottle of wine about the superior Pride & Prejudice remake. My daughter sports a t-shirt that displays Catherine de Bourgh’s infamous quote—“Obstinate, headstrong girl!”—to her jiu jitsu class. It’s a love that’s woven its way through my adulthood. And during these years, I’ve finally had time to consider what keeps me–along with so many others–hooked.

I usually end up back at that Austen’s quote, and the inevitable question in spawns: if Emma is unlikeable, why do we love her so much?

That’s what Austen promised. A love story for imperfect, “unlikable” women who hold strong opinions and make mortifying mistakes.

The topic of unlikeable female protagonists seems ubiquitous these days. From books to television to film, it’s a trope that’s on the forefront of pop culture. But while the merits and depictions of the “unlikeable woman” are discussed and dissected, there seems to be less discussion as to what defines her to begin with, and who gets to decide. And that’s probably because the answer is as obvious as it is uncomfortable (hint: it’s men).

The unlikeable woman trope isn’t new. Independent, bawdy women have appeared in Western literature since we first put pen to paper. But in popular novels like Daniel Defoe’s Roxana and Eliza Haywood’s Love in Excess, these women—as well as the incredibly dramatic events that occur to them–exist outside of social norms. And while that made for entertaining literature, it was more likely to be cautionary than relatable to the average reader.

But what about real life? Not torrid affairs with foreign princes or gruesome murders of romantic rivals, but everyday events in the domestic realm, the very place where so many women of the time were tethered?

Enter Jane Austen.

With characters like Elizabeth Bennet, Marianne Dashwood, and Emma Woodhouse, readers found something entirely new: complex women who maintain their agency, living in a place that was familiar, who still get a happily ever after.

This was radical.

It wasn’t just that romances in the domestic sphere were rare, but that these female protagonists were even more so. These women had flaws and made mistakes, but they also didn’t require redemption in order to attain happiness. They learn about themselves and grow as people, but that knowledge doesn’t require a fundamental change in their personality. We know their thoughts and feelings, sympathize and relate to their struggles, and ultimately share in their happiness.

It was the birth of the modern romance novel.

Of course, even in the time of Austen, romance novels weren’t new. But ones in a domestic setting? Featuring “unlikable” female protagonists? That was unheard of. Because for it to be a romance, there has to be a woman who is likable to someone, right? Otherwise, who would fall in love with them?

Austen had an answer for that too: George Knightley. And Fitzwilliam Darcy. And Colonel Brandon. Men that didn’t require the women they love to change. In fact, many times it was the men that had to bend: open their minds and grow to win the heart of the protagonist.

That’s what Austen promised. A love story for imperfect, “unlikable” women who hold strong opinions and make mortifying mistakes. In short: women just like us.

No other novel encapsulates this better than Emma. It’s not just that Austen knew how Emma’s traits would make her unlikable in 1814, but that those traits are still so relatable today. Who among us wasn’t absolutely sure we had the world figured out when we were 20 years old? Or said something mortifying that we still cringe to think about? Even the parts of her character that are less relatable are nonetheless familiar, like the fact that financially independent woman who don’t want to get married are still having to defend their decisions.

Sure, “unlikable” might equate “bad” to the men doing the math, but to the rest of us, it’s quite the opposite. By creating female protagonists that are flawed but aren’t required to somehow fix those flaws in order to be loved, Austen gave “unlikable” women space for their mistakes, value to their independence, and hope for a happily ever after.

So, like I said, Ms. Austen was right. Emma is unlikable. And that’s okay. Because while some people might not like Emma, we love her. Because she’s just like us.

__________________________________

Emily Harding is the co-author of Emily of 83rd Street, available now from Gallery Books.