The Snapshot: Kodak Fiends & Their Legacy

Yesterday Google notified me that I have a newly curated album to check out. Responding to the message took me to the app, where I found myself staring at an album titled “Spotlight on Megan.” If you are unfamiliar with Google’s curated albums, these algorithm-produced photo albums are a bit of a mixed bag. Some are endearing, welcomed reminders of past events. Others—like this recent creation—are troubling.

Innocuous on the surface, the album contained roughly twenty photographs of me, pulled and cropped from my pictures and albums shared with friends and family. The troubling part was not that Google thought I would enjoy a self-dedicated album. Rather, it was how well Google’s facial recognition technology had successfully identified my face across these images. Even though such technology is commonplace now, I still find myself taken aback by how little privacy there is in the internet age. While I imagine privacy as an issue directly tied to algorithms, data sharing, and unwanted social media tags, privacy concerns in the world of photography have been around since the medium’s infancy.

The Kodak Fiend

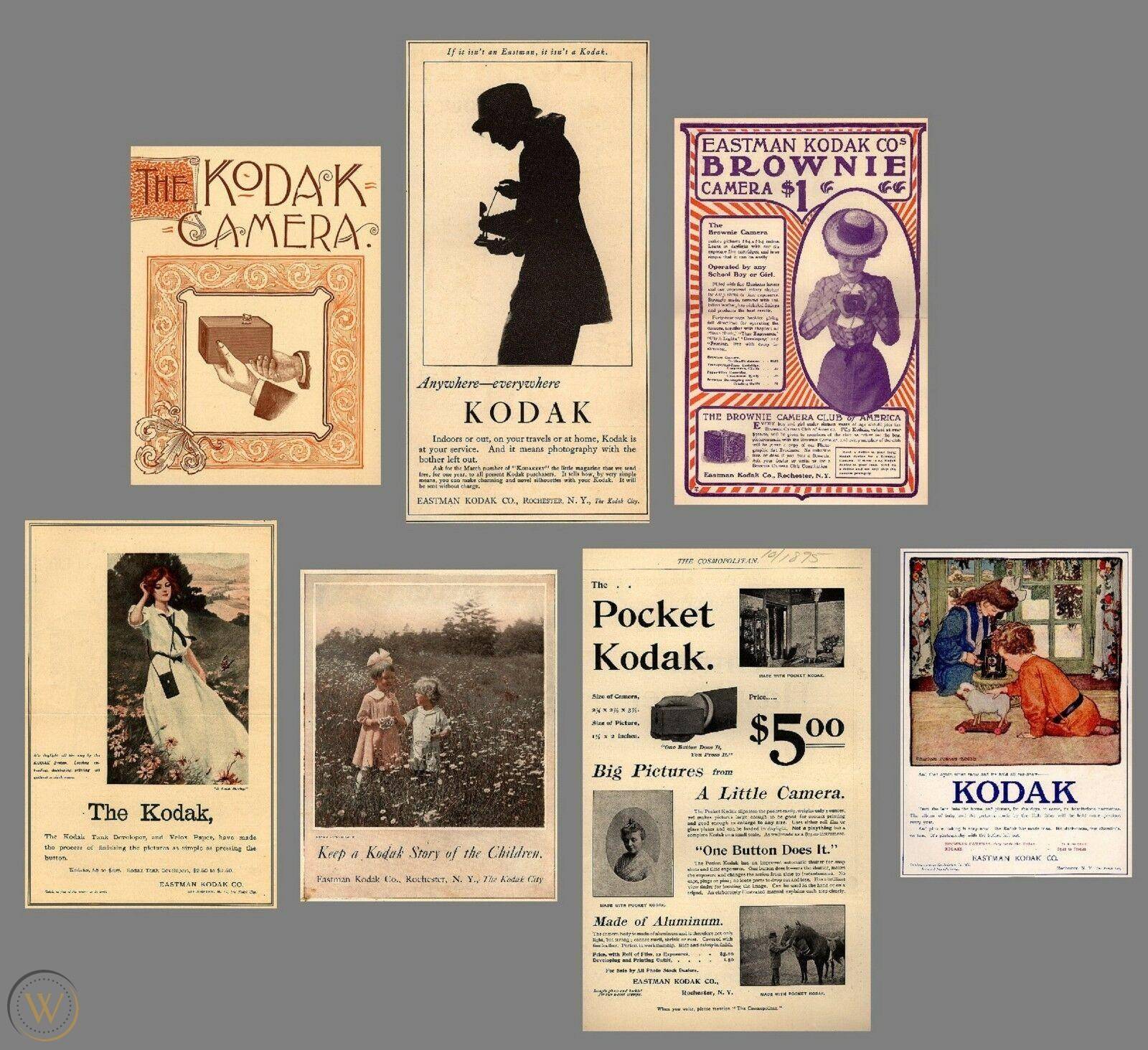

In 1895, George Eastman’s Kodak company introduced the Kodak Brownie. This small, handheld single-lens camera took the guesswork out of shooting photographs and helped jump-start the photo-processing industry. Mass-produced to be an affordable answer to Kodak’s early forays into making cameras, this portable box camera sold for $1 (roughly $30 today). Until this point, photography had been a medium of the affluent and well-connected, limited to professionals or those rich enough to dabble in new technologies. The Brownie turned this all on its head, democratizing photography overnight.

Within a few scant years, photography had become a significant pastime for many. Camera clubs flourished in Europe and the United States as photographers took to the streets en masse, traveling in groups on foot or bike, roaming cities for things to photograph. Photography reached a fever pitch in the early 20th century. Photography books, clubs, exhibitions, and magazines spread across America. Unfortunately, not everyone welcomed this growth.

As photographers spread into the streets, no one was safe from having their picture taken. Many early photographers shot indiscriminately, producing documentary photographs that tracked their lived experiences. For some who would be captured in these images, this little camera represented an invasion of privacy. Much like today, many individuals did not wish to have their photographs taken without their consent. Most upper-class individuals found street photographers irksome—dubbing them “Kodak Fiends.”

These privacy-focused individuals wanted photographers to recognize common decency and decorum, admonishing gawkers for taking photos on beaches and glibly snapping photos at accident scenes. Some would strip photographers of their cameras or threaten them with violence if they did not hand over the exposed film. It is said that President Theodore Roosevelt snapped at a young boy who photographed him while leaving his church after worship.

Because of indiscriminate photographers, privacy concerns grew. As a result, photography was briefly banned in some public spaces, like the Washington Monument and private beaches.

Fighting for Privacy

Sensing a growing need for laws that addressed privacy, two attorneys published an article in the Harvard Law Review that took direct aim at Kodak Fiends. Titled “The Right to Privacy,” Samuel D. Warren and Louis Brandeis (a future Supreme Court justice) made a case for protecting the privacy of individuals by ensuring they owned their own image. In language that seems quaint, they stated their fears regarding photography and gossip: “Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprises have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.’”

The duo advocated for laws to guarantee individuals more control over the use of their likeness and the manipulation of their image. This fight continued for decades as states slowly adopted personal privacy laws. Now considered a right, privacy laws have permeated our lives—protecting our personal information in business, education, health care, and other public settings.

Photography Moves On

The shift in attitudes regarding appropriate photography subjects affected the history of photography. Some historians have suggested that we see many working-class images in the early 20th century due to these laws. Less privileged persons were unlikely to protest having their picture taken and were less able to enforce their wishes. As a result, documentary photography turned toward urbanization. Social documentarians emerged that represented the stories of those previously overlooked, like Paul Martin, John Thomson, and Jacob Riis. Seeking the unexpected in the daily monotony of life, these photographers and their amateur counterparts used photography to evoke the character of modern life.

While much has changed in the intervening century, many of the same concerns are still relevant. Now high-quality cameras are built into our phones, which can share images and videos nearly instantaneously. As a result, we may regularly photograph strangers and public figures, sometimes with—but often without—their permission. In addition, many of us welcome major companies into our lives, allowing their algorithms to track our online and offline behaviors. Gone is the Kodak Fiend. Now we have influencers, photojournalists, paparazzi, and ourselves to worry about, snapping away indiscriminately.

I deleted the Google album mentioned earlier and quickly searched “how to stop Google facial recognition.” Of course, the times have changed, along with the technology, but somehow the same concerns feel pertinent.

Megan Shepherd is a curator, freelance writer, and artist. She has worked in fine art museums for a decade and holds two master’s degrees in the field. When she takes a break from art, she enjoys science-fiction books, antiquing, backpacking, and eating her weight in Dim Sum.

WorthPoint—Discover. Value. Preserve.

The post The Snapshot: Kodak Fiends & Their Legacy first appeared on WorthPoint.